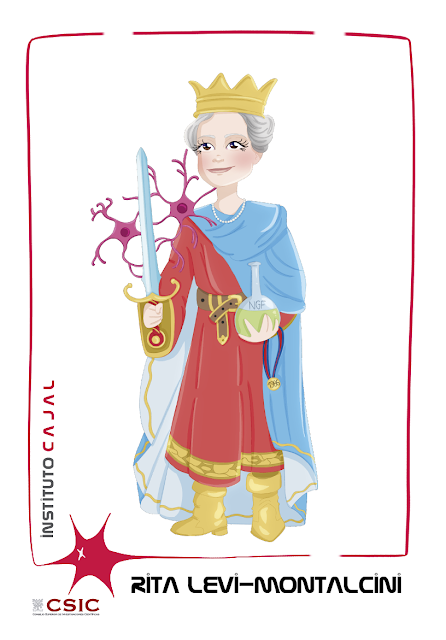

QUEEN OF SWORDS

RITA LEVI MONTALCINI

Queen of Swords: Rita Levi Montalcini (1909 – 2012), the great lady of neuroembryology

Rita Levi Montalcini dedicated her life to unraveling the mysteries of nervous tissue and fought tooth and nail to defend women’s education, science and… to subdue the right hemisphere of the brain! This great Italian lady revealed to us the secrets of neuronal growth factor, pain and programmed cell death. With them the world discovered an unconventional queen 😉, with brilliant conscience and contagious commitment. This is the story of a 103-year-old vocation that has left its mark.

We have raised Rita Levi Montalcini (1909 – 2021) to the throne of the Queen of Swords of the neurodeck. This incredible neuroscientist became a Nobel Prize winner in Physiology or Medicine despite being born a woman into a Jewish family in Mussolini’s Italy and the Europe of World War II. She overcame enormous obstacles with determination and passion to become, not only a brilliant researcher, but an influential humanist woman, focused on promoting scientific education for women around the world and fighting for the eradication of antipersonnel mines.

The piercing cries of a newborn that were heard on April 29, 1909 in a home in Turin (Italy) were those of Rita Levi Montalcini, who had just been born by the hand of her twin Paola. The newcomers did so within a wealthy Jewish family of Sephardic origin, interested in the arts and sciences. Her father, Adamo Levi, was an electrical engineer and mathematician, and her mother, Adele Montalcini, a famous painter. A good genetic and epigenetic heritage to start life well, don’t you think?

The young Rita soon revealed her character when she decided to move away from the role of mother and wife to which her father intended to assign her. Although it may seem strange in a cultured family, Don Adamo Levi tried to resist his daughter pursuing higher education. But from a very young age, Rita was a lot of Rita and overcame her father’s opposition by working in a bakery to, stubborn and tenacious, enroll in medicine at the University of Turin in 1931—with her cousin Eugenia—thanks to the income she earned from her I work as a baker.

The fact is that in 1936 he finished his degree in Medicine and Surgery with the highest grade and, when he had begun his advanced studies in Neurology and Psychology with his former professor Giuseppe Levi, the fascist leader Benito Mussolini forbade any non-Aryan person to have a scientific or professional career. As a Jew, Levi Montalcini was expelled from her school. But her career as a researcher could not end here. Rita was not deterred and went to Belgium where, from 1938 to 1940, she continued studying in Brussels until the advance of German Nazism forced her to return to Italy. Back in her country of origin, the tenacious scientist set up her own clandestine laboratory in one of the bedrooms of her family home, of which Giuseppe Levi himself would become a part. With the help of tools that had nothing to do with her new mission, such as watchmaker’s pliers or sewing scissors, she studied the growth of nerve fibers in chicken embryos.

But the bombs of World War II arrived in Turin and the researcher moved to the countryside with the laboratory in tow. Later, the Germans arrived with their anti-Semitic persecution and the Levi-Montalcini family fled again, this time to the south of the country until the end of the war. After the liberation of Italy, Rita Levi Montalcini worked as a doctor in the concentration camps until, in 1945, she was able to return to her laboratory in Turin and resume her research as Levi’s assistant.

Nobel research

The work of Rita Levi Montalcini together with Giuseppe Levi was already quite well known once the war ended. Both devised a theory about embryonic nerve cells that laid the foundation for the conception of programmed cell death (or apoptosis) as part of the normal development of the nervous system.

Therefore, in 1946, the researcher was invited by Viktor Hamburger (1900 – 2001) to Washington University in St. Louis (USA). Hamburger’s work on how nerve cells connect had served as inspiration for the Italian’s research, although she later contradicted the scientist’s conclusions.

It was in this laboratory where Rita Levi Montalcini wrote part of the history of Neurology. Together with Hamburger, she observed that a particular type of mouse tumor stimulated vigorous nerve growth when implanted into chicken embryos.

Determined to discover the cause, the scientist went with her mice to the University of Brazil where, in 1952, she managed to isolate the substance behind such an effect. This was called nerve growth factor (NCF). For her discovery, Rita Levi Montalcini received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1986 along with Stanley Cohen. Cohen’s role was to determine the nature of the NGF: a protein. The snake venom helped him reach such a conclusion.

The FCN is key for the development, differentiation, growth and survival of neurons. It also helps the single cell formed by the union of an egg and a sperm to generate the specialized cells that make up our body.

The work of Rita Levi-Montalcini, which practically dealt with this protein, has therefore been vital to understanding the processes of neurodevelopment. But also for the treatment of diseases. FCN has an important role in tumors and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s, as well as in pain and inflammatory processes.

Understanding inflammation would not have been possible without the researcher’s scientific achievements. In addition to explaining the role of FCN in this process, Rita Levi Montalcini described the mechanism called ALIA (Autacoid Local Injury Antagonism), which is currently key for the treatment of neuropathic pain. This mechanism regulates the function of non-neuronal cells (such as microglia and mast cells) that induce and maintain inflammation through the production of a molecule known as palmitoylethanolamide (PEA). This substance is a fatty acid that is widely studied for its anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects. Due to its effects on metabolism, behavior, inflammation and pain perception, PEA is a substance that could have therapeutic effects in different neurodegenerative diseases.

Commitment to science

Levi Montalcini is the oldest Nobel laureate in history and she was a tireless researcher until the end of her days. So much so that at the age of 98 – she died at 103 – she embarked on what would be her last research project studying her star protein.

However, her commitment to science went much further. Throughout her long life, the neuroscientist was involved in promoting research, with a special focus on young people and women. With this purpose she created, together with her twin Paola de ella (who followed her maternal artistic vein), the Rita Levi-Montalcini Foundation, aimed at promoting the education of women in Africa.

Additionally, she Levi Montalcini founded and was the first director of the Italian Institute of Cell Biology and created the European Brain Research Institute, both based in Rome. Politics was not left out of the scientist’s ambitions, because in her native Italy she became a senator for life, a position from which she legislated in favor of the promotion of science in society.

Rita Levi Montalcini was that “endearing grandmother” of nerve cells who took the world by storm with Italian elegance and Sephardic power. She always unsheathed the sword of science to cut off any type of prejudice and clear the field of women’s education of obstacles as a safe passage for her freedom. Close and direct, as she said, with her death only her little body has disappeared, but her mark remains. Thanks, Rita!

THE CONTENT OF THIS POST WAS MADE IN COLLABORATION WITH LEYRE FLAMARIQUE, WITHIN THE CSIC-BBVA FOUNDATION FOR SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION AID PROGRAM

Have you been curious and want to know more?

ALONSO, José Ramón. History of the Brain. A history of humanity. Pages dedicated to Rita Levi Montalcini «The Lady of the Cells» [pp. 678-682]

Blog In the country of the latest things.

https://enelpaisdelasultimascosas.blogspot.com/2010/05/rita-levi-montalcini.html

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aloe, L., Leon, A., & Levi-Montalcini, R. (1993). A proposed autacoid mechanism controlling mastocyte behavior. Agents and actions, 39(1), C145-C147. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01972748

Cohen, S., & Levi-Montalcini, R. (1956). A nerve growth-stimulating factor isolated from snake venom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 42(9), 571. https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.42.9.571

Cohen, S., Levi-Montalcini, R., & Hamburger, V. (1954). A nerve growth-stimulating factor isolated from sarcomas 37 and 180. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 40(10), 1014. https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/ pnas.40.10.1014

Goldstein, B. (2021, December 1). A Lab of Her Own by her. Nautilus. https://nautil.us/a-lab-of-her-own-13306/

Iversen, L.L. (2013). Rita Levi-Montalcini: neuroscientist par excellence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(13), 4862-4863. https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1301976110

Levi-Montalcini, R. (1987). The nerve growth factor 35 years later. Science, 237(4819), 1154-1162. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.3306916

Levi-Montalcini, R. (2017). Your future: Advice from a Nobel Prize winner to young people. Platform.

Levi-Montalcini, R., & López, D. P. (2013). Dare to know. Criticism.

Levi-Montalcini, R., & Salmerón, J. M. (2011). Praise of imperfection. Barcelona: Tusquets.

Levi-Montalcini, R., Dal Toso, R., della Valle, F., Skaper, S. D., & Leon, A. (1995). Update of the NGF saga. Journal of the neurological sciences, 130(2), 119-127. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0022510X9500007O

Navis, A. R. (2007, November 1). Stanley Cohen (1922- ). The Embryo Project Encyclopedia. https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/stanley-cohen-1922

Navis, A. R. (2007, November 8). Rita Levi-Montalcini (1909-2012). The Embryo Project Encyclopedia. https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/rita-levi-montalcini-1909-2012

Raso, G. M., Russo, R., Calignano, A., & Meli, R. (2014). Palmitoylethanolamide in CNS health and disease. Pharmacological Research, 86, 32-41. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1043661814000656

The Nobel Prize. Press release https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1986/press-release/

The Nobel Prize. Rita Levi-Montalcini Facts https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1986/levi-montalcini/facts/

The Nobel Prize. The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1986 https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1986/summary/

The Nobel Prize/ Series Women who changed science RITA LEVI-MONTALCINI Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1986. https://www.nobelprize.org/womenwhochangedscience/stories/rita-levi-montalcini

Bradshaw, R. A. (2013). Rita Levi-Montalcini (1909–2012). Nature, 493(7432), 306-306. https://www.nature.com/articles/493306a

VIDEO Biography

Cool YouTube Channel: The Most Extravagant Nobel Prize Winner Who Lived to 103 https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=qGLtGhuIpIU&feature=emb_logo