QUEEN OF CUPS

MARIAN DIAMOND

Queen of Cups: MARIAN DIAMOND (1926-2017), the lover of the brain who revealed its plasticity to the world

Marian Diamond was born to change neuroscience. She was fascinated by “the most wonderful structure on Earth”, capable of making us what we are: the brain. In love with that object, which she carried to her classes inside a hat box, her research demonstrated something that Cajal already intuited at the end of the 19th century: brain plasticity and the important role of neuroglia. She herself was the best example that to keep the brain in shape you have to use it and season it with five ingredients: good nutrition, physical exercise, challenges, novelty and… love!!!

«The brain is the most miraculous mass of protoplasm in the world and, perhaps, in the entire galaxy. Its potential is virtually unknown” (Marian Diamond)

Marian Diamond was born on November 11, 1926 in Glendale, California (USA) and was the youngest of six children. Her father, Montague Cleeves, worked as a doctor and her mother, Rosa Marian Wamphler, left her doctoral studies to raise their children. The family lived in a summer environment surrounded by fruit trees, goats and chickens.

Diamond spoke of the human brain as if it were the greatest jewel in the universe. And that’s how it was for her. A visit with her father to the Los Angeles County Hospital planted a seed that would not stop growing throughout her life. The neuroscientist was 15 years old at the time. She walked alongside her mother, passing the closed rooms of the hallway they were walking through. But one of those doors was ajar. There, laid out on a table like a trophy, was a human brain. It was the first that young Marian had seen. Those cells can create ideas, she thought. A notion that was more than enough for the researcher to know that, if she studied something, she would study brains.

So Diamond enrolled at Glendale Community College and then moved on to the University of California (Berkeley, USA) in 1946. That would be her home for decades to come. There she completed her doctorate in anatomy, becoming, in 1953, the first woman to obtain it at that center.

Diamond combined her doctoral studies with her work as a teacher, developing a lifelong passion. She also challenged the prevailing machismo in this area. Diamond was the first woman professor of science at Cornell University (USA) where she taught human biology and comparative anatomy until 1958. From there, she would take her teachings to the University of California (San Francisco, USA). ) and then returned to Berkeley in 1960.

At Berkeley she continued her classes, along with her studies in brain anatomy. Marian Diamon’s obsession with the brain was such that she changed the idea we had of this organ and revolutionized the panorama of neuroscience.

A moldable brain

Although Cajal’s first speculations that learning requires the formation of new connections between neurons date back to 1894, in the 1960s the brain was still seen as static, genetically determined and without the possibility of change throughout life. Marian Diamond set out to prove the opposite, since she was aware of a study that established the existence of chemical changes in the adult brain of mammals and raised the possibility that structural physical changes also occurred there.

“Every man can be, if he sets his mind to it, a sculptor of his own brain” (Santiago Ramón y Cajal)

The scientist had joined a team of three researchers at Berkeley who were looking for evidence that the brain was affected by the environment and was not solely predetermined by genetics. The group consisted of psychologists David Krech and Mark Rosenzweig, and chemist Edward L. Bennett. Diamond completed the quartet by becoming the anatomist of a team that worked side by side for the next 15 years.

Marian devised some very simple, but effective experiments for her research. She raised rats in different environments. Some lived communally in a large cage—rats are very social animals that enjoy company as much as we do—and surrounded by toys. A real amusement park for rats 😉. Others lived alone in a small cage with nothing to entertain themselves. The question Diamond asked himself was: What do each of these environments produce in the rat brain?

The results took years, but they were spectacular. With enrichment—toys, company, and space—the brain increased in size and with impoverishment, it decreased. The finding implied that the organ is not completely determined at birth. There was opportunity for change: it was plastic. This was something that had never been seen before! Diamond ran across campus to show Krech the results. “This will change science,” the psychologist told him.

The paper on plasticity in rat brains was published in 1964. Women were a rare find in research, so David Krech wrote Marian Diamond’s name at the end and in parentheses. His argument was that he had never written with a woman and that he didn’t know what to do. Fortunately, he reconsidered after her wake-up call and put Diamond as her first author.

Marian’s research shook, cracked and turned upside down the prevailing conception of the brain. Although penetrating such a revolution into the foundations of neuroscience at that time was not easy. It didn’t make any sense to people at the time that the brain had changed because of the environment because of something called “plasticity.” It was a revolution in the prevailing paradigm.

Brain plasticity has become, however, one of the central terms of modern neuroscience. With Diamond’s challenge to the accepted theories of his time, the brain became a moldable organ. In fact, the researcher’s leitmotif was: You use it or you lose it (something like “Either you use it or you lose it”).

In addition to initiating a field of knowledge and research, Diamond also indirectly drove cultural change. The concept of an enriched environment is something that anyone has applied or can see examples of: babies with toys in which they have to learn to fit shapes, addicted to Sudoku puzzles to keep their minds active or that “get out of the zone” comfort”. Diamond even established the five ingredients of the recipe for having the “best possible version” of the brain: a good diet, physical exercise, challenges, novelty and love.

The incorporation of the fifth ingredient, love, came due to a methodological necessity: to study plasticity in aging they needed to experiment with older rats than those available in her laboratory. But they only got rats that were about 600 days old (equivalent to about 60 human years). They lacked love. So they began to give them careful and loving treatment. In this way, they managed to ensure that some specimens lived up to 900 days (about 90 human years). And at that age they found that the rats still showed changes in the brain thanks to neuroplasticity, another milestone for science. These results were published in 1985.

Einstein’s brain and glial cells

As a lover of brains, the scientist could not help but notice the most sought-after brain in history: that of Albert Einstein. Diamond read in Science magazine that the physicist’s brain was preserved and stored in glass jars. So she asked if she could pick up four pieces in which she would study a series of areas that she could compare with those of brains of humans of normal intelligence. She told him yes.

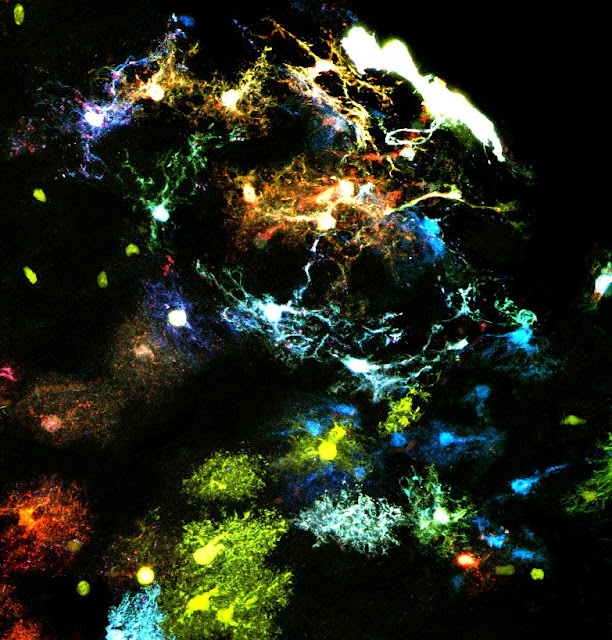

In 1984, 29 years after Einstein’s death, Marian Diamond and her colleagues were the first to publish research on the scientist’s brain. They found that there was no such thing as special neurons that would have made him a genius. On the other hand, they did observe that glial cells were much more abundant in one of the four small fragments studied. As expected, these results were not without controversy, since the scientific methodology had certain limitations, but it had the merit of underlining the enormous importance of neuroglial cells, cells that no one considers as simple assistants of neurons but rather , rather, as fundamental elements of cognition. In fact, as we already explained in the Ace of Cups entry, it is currently known that astrocytes communicate through a calcium signaling system.

Since Pío del Río-Hortega described microglia and oligodendroglia at the beginning of the 20th century, there has been progress in the knowledge of neuroglia. We now know that it plays a relevant role in key aspects of brain functioning, such as cognitive functions.

Células gliales procedentes de células madre marcadas en el cerebro de ratón con códigos de color únicos (Dra. Laura López Mascaraque, Instituto Cajal, CSIC)

A passionate (and famous) teacher

Marian became famous as a teacher because she always brought a colorful hatbox to her classes. With a hypnotic ritual, the scientist opened the hatbox, put on the latex gloves that she left prepared inside it and opened a container from which she extracted what she considered her greatest treasure: a human brain. She would take it out to hold it in the palm of her hand, talking about it with a fascination that the passing of the years never diminished.

Diamond’s classes made you laugh, think, reflect, question… Perhaps that was the secret of her success, which extended far beyond the classroom — the teacher received mail from all over the world thanking her for her lessons. In 2005, Berkeley University posted Diamond’s Introduction to Anatomy course on YouTube. More than four million views made it the second most popular online course in the world, behind Moral Reasoning from Harvard University. She is currently among the 10 most viewed teachers on the web.

In June 2014, Marian said goodbye to her Berkeley office. At 87 years old, the scientist had been teaching passionately since 1954. During those 60 years, Marian made some 60,000 students vibrate directly with her science, and indirectly to the millions of people who watched and continue to watch her videos.

She was, and she will be remembered, as a vital and competent teacher, as she herself indicated that she would like to be, who loved to share knowledge and experiences with her students and offer them information that was useful to them.

With contagious joy and passion, Ella Diamond said she had spent “more than 60 years studying the brain” and “pure joy.”

THE CONTENT OF THIS POST WAS MADE IN COLLABORATION WITH LEYRE FLAMARIQUE, WITHIN THE CSIC-BBVA FOUNDATION FOR SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION AID PROGRAM

Have you been curious and want to know more?

SOURCES CONSULTED

Luna Productions (2016). My Love Affair with the Brain. The life and science of Dr. Marian Diamond. Available at: https://vimeo.com/417009456?login=true#_=_

Sanders, R (July 28, 2017). Marian Diamond, known for studies of Einstein’s brain, dies at 90. Berkeley News. https://news.berkeley.edu/2017/07/28/marian-diamond-known-for-studies-of-einsteins-brain-dies-at-90/

Diamond, M. C., Johnson, R. E., Protti, A. M., Ott, C., & Kajisa, L. (1985). Plasticity in the 904-day-old male rat cerebral cortex. Experimental Neurology, 87(2), 309-317. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-4886(85)90221-3

The New York Times (April 18, 2010) What They’re Watching https://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/18/education/edlife/18opentop10-t.html

Geoffrey Neill. Marian Diamond on Building a Better Brain. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ci0xcM2rgzY&ab_channel=GeoffreyNeill

Webcast-legacy Departmental. Integrative Biology 131. Marian Diamond full course. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S9WtBRNydso&list=PLYaP1u75QsCDt6gTE29X758sD7-by7U_T&ab_channel=Webcast-legacyDepartmental

Diamond, M. C., Krech, D., & Rosenzweig, M. R. (1964). The effects of an enriched environment on the histology of the rat cerebral cortex. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 123(1), 111-119. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.901230110

Diamond, M. C., Scheibel, A. B., Murphy Jr, G. M., & Harvey, T. (1985). On the brain of a scientist: Albert Einstein. Experimental neurology, 88(1), 198-204. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-4886(85)90123-2

Gamundí, A. G., & Gamero, A. F. (2006). Santiago Ramón y Cajal: 100 years later. Universitat Balearic Islands.

OTHER INTERESTING LINKS:

Marian Diamond’s collaborators:

Mark Rosenzweig https://es.abcdef.wiki/wiki/Mark_Rosenzweig_(psychologist)

David Krech https://es.abcdef.wiki/wiki/David_Krech

Edward L. Bennett https://www.researchgate.net/scientific-contributions/Edward-L-Bennett-38912323

YouTube Channel Cerebrotes, by Clara García, Neuromitos series

Is it true that new neurons cannot form in the adult brain? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kt86gcwAD3c

Neuroplasticity:

What is neuroplasticity? https://academianeurona.com/neuroplasticidad/

DeFelipe, Javier (2006). Brain plasticity and mental processes: Cajal again. Nat Rev. Neurosci. 2006 Oct;7(10):811-17.

Interview with Álvaro Pascual-Leone in El País (Jessica Mouzo, 03/13/2017): Your brain changes with everything you think, even if you don’t say it https://elpais.com/elpais/2017/03/08/ciencia/ 1489000861_407908.html

Origin and development of neuroplasticity (1) https://www.investigacionyciencia.es/blogs/psicologia-y-neurociencia/100/posts/origen-y-desarrollo-de-la-nocin-de-neuroplasticidad-1-15679 #:~:text=Origin%20and%20development%20of%20la%20noci%C3%B3n%20of%20neuroplasticity, use%20repeated%20a%20through%C3%A9s%20of%20los%20h%C3%A1bites%20behavioral.

Origin and development of neuroplasticity (2) https://www.investigacionyciencia.es/blogs/psicologia-y-neurociencia/100/posts/origen-y-desarrollo-de-la-nocin-de-neuroplasticidad-2-15704

YouTube Channel Cerebrotes, by Clara García

Neuromyths: Is it true that new neurons cannot form in the adult brain? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kt86gcwAD3c

Why can’t neurons divide? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-kef23WOWPM&t=68s

Neuroplasticity and neuroplasticity in action: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DtACi3Ht7Ro

Neurorepair. Interview with José Ramón Alonso (neuroscientist and professor at the University of Salamanca) https://www.investigacionyciencia.es/blogs/psicologia-y-neurociencia/100/posts/jos-ramn-alonso-pea-neurorreparacin-17192